Demonstrators carry a sign with a famous quote from civil rights activist Ella Baker at a demonstration shortly after the murder of George Floyd in 2020. In the years since, brands have donated billions in pursuit of racial equity, but it's often unclear how much Black communities really benefited. (Image: Nathan Dumlao/Unsplash)

Many brands will mark Black History Month by announcing new investments aimed at supporting Black communities. But how will they measure the results? A coalition of Black-led community development financial institutions (CDFIs), credit unions and venture capital firms has a tool that can help, but few financial companies actually use it.

The African American Equity Impact Scorecard uses a set of metrics to help financial institutions assess if the investments they make actually have an impact in Black communities. It was created by the African American Alliance of CDFI CEOs, which represents 76 Black-led financial institutions serving all 50 U.S. states.

"The scorecard could be a game-changer," says Lenwood V. Long Sr., CEO of the Alliance. "We have areas that look at the health, economic, and governance strength of CDFIs, foundations and banks to measure the impact of those who say they’re investing in Black communities."

Since it rolled out last year, 24 financial institutions have used the scorecard to assess their investments, and leaders at these organizations say the findings were eye-opening. At a time when unprecedented funds are being directed in pursuit of racial equity, it's more critical than ever to ensure those investments actually reach Black communities and make them better, Long says.

Brands need to learn from their mistakes

Unlike big banks and other mainstream financial companies, U.S. federal regulations require CDFIs to channel at least 60 percent of their investments toward underserved low- and middle-income communities. That comes in the form of affordable financial services for low-income people, loans for entrepreneurs, investments in new affordable housing and backing for development projects that create jobs.

Black-led CDFIs in particular make most of their investments and loans directly within the Black communities where they do business. But even as a record level of capital was earmarked for racial equity in the summer of 2020, Black-led CDFIs didn't see much of it.

"You look at the money that came out — that just flooded the streets on the pretense of racial reckoning after the death of George Floyd — if you track that money, that money didn't go a lot to Black organizations," Long remembers. "It went to a number of organizations who said they were ‘serving the Black community.’ That's where those funds went."

As of 2023, companies had committed an estimated $340 billion in support of racial equity in the U.S., but analyses found that many of the commitments were light on details about how funds would be deployed.

Rather than partnering with Black-led organizations already doing the work, many of these investors created their own (white-led) nonprofits or foundations and put their money there, Long says. Others sought out national nonprofits or larger CDFIs they perceived as having more established track records which were, again, predominantly white-led.

Even if well intentioned, the results only entrenched existing disparities that leave Black-run organizations undercapitalized and unable to govern the funds supposedly meant to improve their communities. White-led CDFIs, for example, own more than six times the assets of Black-led CDFIs in the U.S., according to 2020 research from the Hope Policy Institute.

"If you ask, 'Where did that come from?' It's racist investment. That's where it came from," Long says. "Until we stop this nonsense about 'we are fair, we are equitable,' it just won't happen. If these institutions looked at their balance sheets and how they’re investing in Black- and white-led organizations, they’ll find out they’re part of the problem."

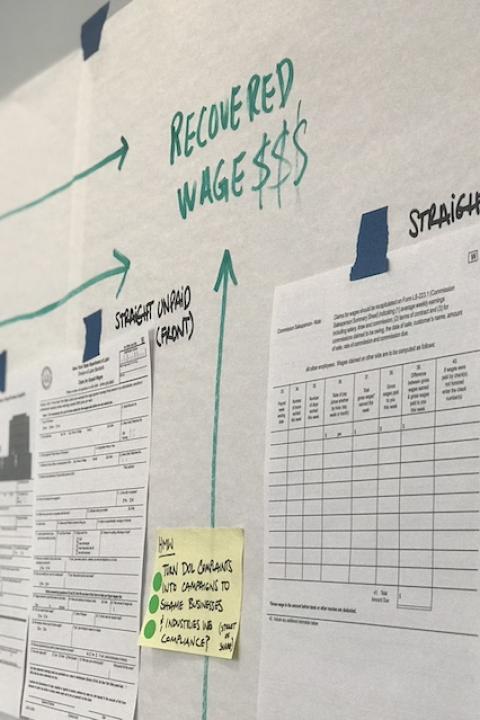

This search for visibility into the tangible outcome of billions in investments inspired the creation of the scorecard, and it's already changing how some financial companies do business.

"It is up to us to use it to hold ourselves accountable to Black communities"

The scorecard takes the form of a questionnaire to measure investments across five categories — including how well they reflect the needs and wants of the community, how they address historic disparities, and how they create well-paying jobs.

Though quick to make flashy announcements about big-dollar investments, large financial institutions in general — and white-led financial institutions in particular — have been slower to assess outcomes. "When you look at the scorecard, I call it looking in the mirror," Long says. "And that’s why the white institutions don’t want to look at the scorecard, because they don't want to see the results of it."

While some are resistant, the co-creator of the scorecard is actually a white-led CDFI, Community Vision out of California. "Until now, mission-driven lenders have lacked a coordinated way to track and report on how capital is being deployed into Black-led and Black-centered projects," says Catherine Howard, president of Community Vision. "Without this important data set, it is difficult to implement strong accountability measures that change investment behaviors."

Community Vision now uses the scorecard to assess all of its investments, totaling around $40 million in loans and grants annually across California. "The African American Equity Impact Scorecard gives us that ability," Howard says. "Now it is up to us to use it to hold ourselves accountable to Black communities."

The data available through the scorecard also moved another white-led community financial institution, Maine-based Coastal Enterprises, Inc. (CEI), to change its lending and investment practices.

"The scorecard has been a catalytic tool for CEI, transforming our learnings about racial equity and impact into action as we reevaluate products and underwriting practices," the company's chief investment officer, Daniel Wallace, told the Alliance in a case study. "The scorecard has helped CEI move toward an anti-racism framework for our lending team as we built the language and understanding around the racial equity impacts of lending."

The scorecard also informed the creation of Maine-specific metrics for the organization, including investment targets that cover child care providers and businesses creating products and service to fill unmet community needs.

"The inclusion of a race-explicit equity lens in our deals, the engagement with our staff around these topics, and outreach to our local community have all helped move us toward building stronger community partners, creating a collaborative culture and buy-in at CEI around racial equity, and adding capacity to undertake this work," Wallace said. "For the financial industry, waiting on racial equity work isn’t an option. This work is necessary for all of us to overcome the structural biases and racism that has been built into the lending industry over centuries, to rebuild and revitalize our communities, and to make economic justice a reality for all our borrowers.”

The scorecard is available for all financial companies, developers and funders, not only CDFIs. And leaders at the Alliance and Community Vision believe it's just what the space needs to channel well-intended investments in a way that actually makes a difference for those they're intended to serve. "Don't run away from looking at yourself," Long says. "What matters is the impact of your investment."

(Homepage image: James Eades/Unsplash)

Mary has reported on sustainability and social impact for over a decade and now serves as executive editor of TriplePundit. She is also the general manager of TriplePundit's Brand Studio, which has worked with dozens of organizations on sustainability storytelling, and VP of content for TriplePundit's parent company 3BL.