(Image: Jsme MILA/Pexels)

Few truths are as essential to being human as receiving and giving care. At some point in our lives, we all need to be cared for and need to assume the role of caregiver. Children require caregiving from parents, and older adults need their families to help them as they age.

More than 1 in 5 Americans are family caregivers. Yet the U.S. faces a caregiving crisis of immense proportion. Support for individuals, families and the care workforce is severely lacking while America is entering an elder boom, with all baby boomers turning 65 or older by 2030. That’s 10,000 people turning 65 every day. Their millennial children are far from ready for this elder care crisis. The prospect of finding themselves in the “sandwich generation,” made up of those caring for elderly parents and young children at the same time, is real.

Caregiving needs to be a collective effort

About 70 percent of people over 65 will need long-term care for an average of three years. Given that one year in a nursing home can cost over $80,000 and is not covered by Medicare, 80 percent of care falls to family members, according to the advocacy organization Caring Across Generations.

And those caregivers are tired. The vast majority (96 percent) reported feeling emotionally drained from the day-to-day challenges of caregiving, according to a recent survey from A Place for Mom, an organization offering guidance for families looking for senior living and home care.

This unsustainable set of circumstances extends into other parts of caregivers’ lives and the economy, including their ability to work. Three-quarters of people who were employed before they became caregivers said they have less time to focus on work or had to quit their jobs to provide care.

It doesn’t have to be this way. Solutions for creating a care economy that works for everyone exist today, provided there is sufficient political will, employer support, public awareness, and individual and collective resolve to change the trajectory.

“I believe caregiving was always meant to be a collective endeavor,” Ai-jen Poo, president of the National Domestic Worker's Alliance and director of Caring Across Generations, told TriplePundit. “It was never meant to be shouldered by individuals within families alone. Because this has been such a simmering crisis for so long, we are all coming to the realization that we need to do more than just ‘woman up and figure it out.’”

Caregivers are stretched to their limits

Women are at the center of the care economy — particularly women of color — making the caregiving crisis an issue of gender, racial and social equity. In the U.S., 4 in 5 care workers are women, and women of color make up a growing segment of this essential workforce. In families, women make up three-quarters of caregivers, according to A Place For Mom.

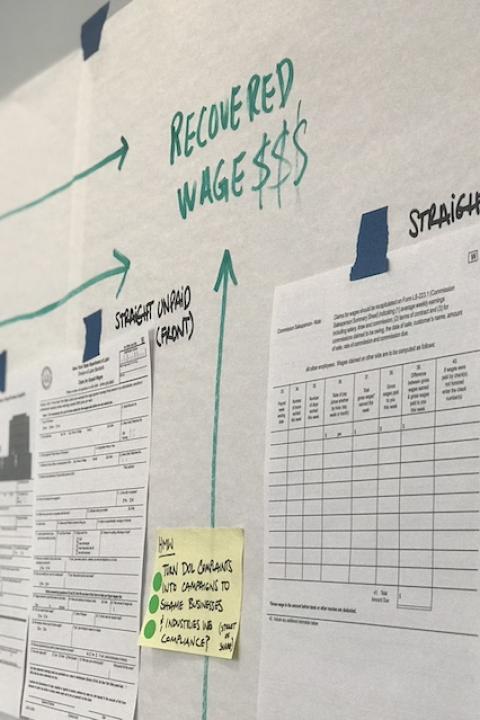

Yet women in both categories lack the conditions necessary to do their jobs well and maintain their quality of life. People of color in the direct care workforce have the lowest family income and lowest annual earnings of any racial or ethnic group, earning an average of $12 an hour with annual wages of only $17,200. Not surprisingly, this leads to a turnover rate of 26 percent.

Low pay and poor working conditions for the paid care workforce, lack of supportive policies for both paid and family caregivers, and the pressure on families and individuals have created a perfect storm that needs to be addressed now, Poo said.

“We have always had people working in the care economy,” Poo said. "Overwhelmingly, they are women. Mostly women of color, immigrant women and women of marginalized social status. It is an essential part of our economy. Yet it has never been adequately compensated or valued such that the workforce charged with caring for our loved ones as their profession — and supporting the rest of us to participate in the labor market — can sustain doing this work.”

Unpaid female caregivers in families also suffer higher-than-average health consequences including stress, burnout, anxiety and depression.

The caregiving crisis also contributes to the epidemic of loneliness and social isolation in the U.S., Poo said. The solution is recognizing that everyone is in this together.

“If we are to find the solutions, this needs to be a collective endeavor,” she said. “We need a strong care workforce, but we also need family caregivers who are supported. We will need respite care. We will need our neighbors, our friends, our communities. Our generational calling is to rise to the occasion and once and for all build the kind of care infrastructure we need so that future generations are not in this position.”

Policy as the foundation of care infrastructure

Just as caregiving was never meant for the individual or family alone, it is not their responsibility alone to fix the problem, Poo said.

“The role of government is to essentially solve for the challenges that are at the level of society that we cannot do on our own, and that the market can't do on its own,” she said. “While I do think that there's a huge role for the market to play, ultimately caregiving is too fundamental a human need for it to be up to the market alone.”

One step in the right direction was President Joe Biden's historic care executive order in April 2023. Just this week, about $37 billion was directed toward home-and-community-based service for millions of seniors and Americans with disabilities. The funding is intended to help providers retain, recruit, and train care workers and provide bonuses and pay increases for them.

Beyond this, advocates must continue to push for affordable childcare, paid family and medical leave, and a universal long-term care benefit, Poo said.

How business can be part of the solution

Business also has a role to play in care economy solutions as roughly 90 million people have care responsibilities outside of their full-time jobs, according to a survey by Boston Consulting Group. Nearly 60 percent of employed caregivers said they struggle with their mental health, their physical health, productivity and burnout. The consulting group estimates the U.S. could lose $290 billion in GDP per year by 2030 due to lost wages and care shortages.

“For any employer having trouble attracting and retaining a workforce, this is just such an obvious measure of diversity,” Poo said. “Imagine the human potential we could unleash if we were able to support people when they went to work each day by understanding their caregiving needs and responsibilities.”

The group of 20 businesses represented in Caring Across Generations’ Business Care Council are on the leading edge of workplace and personnel policies that support parents, family caregivers and disabled people. Among them is Molly Moon Ice Cream in Seattle, which provides 12 weeks of paid family and medical leave to employees.

Molly Moon Neitzel, the company’s founder, testified to the U.S. Congress in 2021 that this policy helped “retain valuable staff members who make us the kind of company that keeps my customers coming back.”

The financial costs of Molly Moon’s paid leave benefit were eased when Washington passed legislation in 2017 that allows the state to pay for a part of employees' paychecks while they are on leave. “Everyone in the country should be able to be covered by a similar social insurance family leave program,” Neitzel said.

Molly Moon Ice Cream’s family leave benefit is a role model for other businesses, Poo said. By federally mandating paid family and medical leave, the government can help level the playing field so that small businesses and businesses that are doing the right thing aren't at a disadvantage.

“It should be the baseline of expectation for our employers and our government that people need to both work and care for the people that we love,” she said. “And that care is also a form of work.”

Based in Florida, Amy has covered sustainability for over 25 years, including for TriplePundit, Reuters Sustainable Business and Ethical Corporation Magazine. She also writes sustainability reports and thought leadership for companies. She is the ghostwriter for Sustainability Leadership: A Swedish Approach to Transforming Your Company, Industry and the World. Connect with Amy on LinkedIn and her Substack newsletter focused on gray divorce, caregiving and other cultural topics.